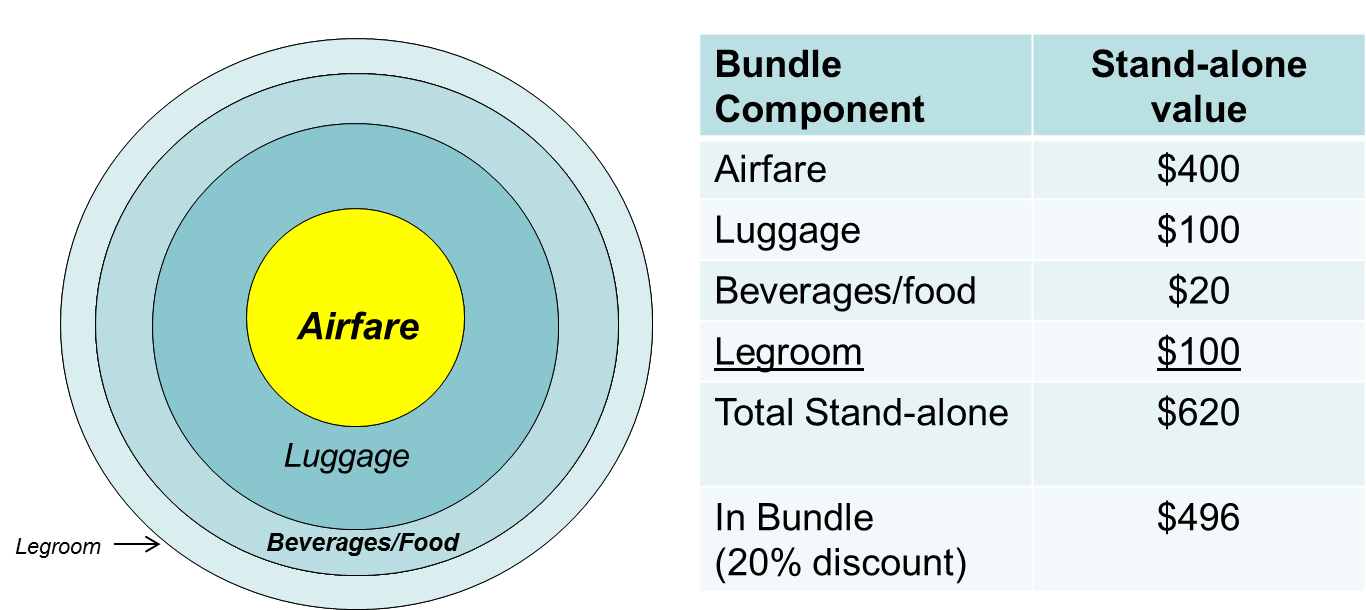

One of the toughest pricing decisions faced by companies is how to trade off the long-term benefits of customer seniority versus the short-term benefits of immediate higher marginal profit by auctioning inventory to the highest bidder.

In this newsletter we’ll explore the impact of these decisions with two industry examples, and under what context favoring loyalty or marginal revenue makes sense.

Airline Industry

The airline industry tackles this problem daily, and the players use different strategies. Most established carriers have frequent flyer programs, which reward flyers with various perquisites, mostly notably the opportunity to be upgraded through a combination of loyalty tier and seniority.

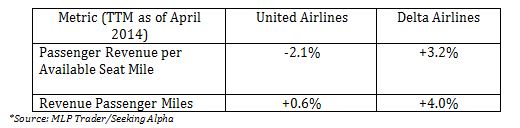

The execution of these programs reveals stark differences, however. Delta Airlines, high tier flyers can secure business class upgrades well in advance of a flight. United Airlines (UAL) contrarily holds business class seats open until much closer to flight departure, allowing less frequent flyers to purchase upgrades, thereby jumping the queue.

The execution of these programs reveals stark differences, however. Delta Airlines, high tier flyers can secure business class upgrades well in advance of a flight. United Airlines (UAL) contrarily holds business class seats open until much closer to flight departure, allowing less frequent flyers to purchase upgrades, thereby jumping the queue.

Loyal and frequent UAL customers detest this as they watch themselves being set aside in coach class for small incremental revenue to UAL. Making matters worse, UAL price discriminates; they purportedly charge the frequent flyer more for the upgrade than a far less frequent flyer because UAL believes the former can pay more! This raises in their minds the value of being a frequent flyer altogether.*

Loyal and frequent UAL customers detest this as they watch themselves being set aside in coach class for small incremental revenue to UAL. Making matters worse, UAL price discriminates; they purportedly charge the frequent flyer more for the upgrade than a far less frequent flyer because UAL believes the former can pay more! This raises in their minds the value of being a frequent flyer altogether.*

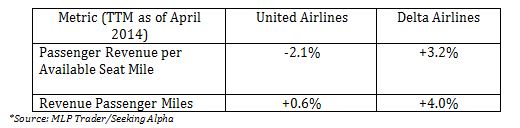

The recent operating results of the two carriers could arguably shed some light on effectiveness of the different philosophies:*

Whilst there are many factors impacting revenue, re-thinking their frequent flyer approach is the major change in the period studied, so it seems that Delta’s approach of rewarding the high frequent flyers may be paying off.

Directory Business

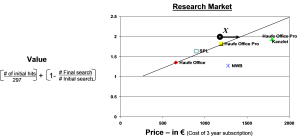

In another example, traditional directory businesses are shifting to a more digitally centric business model. In most cases, online directories do not translate perfectly to print, as users will thumb through print, but are less inclined to scroll through web pages (research shows that the top 6 Google results typically account for 90% of subsequent click through.

Directory businesses thus face the decision on how to award the top listings.

ThomasNet, the well-known industrial directory business, uses an annual auction approach for listing positioning. That is more useful when buyers are sophisticated and have agencies or in house capabilities to manage the Ad Word purchasing cycle. In this approach, marginal revenue is the highest since the market aligns value to inventory.

ThomasNet, the well-known industrial directory business, uses an annual auction approach for listing positioning. That is more useful when buyers are sophisticated and have agencies or in house capabilities to manage the Ad Word purchasing cycle. In this approach, marginal revenue is the highest since the market aligns value to inventory.

Alternatively, for less resourced companies, a single top tier price is set, and seniority drives the placement. This leaves marginal income on the table though as buyers willing to pay more for a top listing can’t.

A hybrid approach would be a “pseudo-auction” where the directory company sets a very high price for top tiers which would by means of high price limit the number of takers, making a short “first page.” In this hybrid approach, marginal income is captured, but senior advertisers may feel the way UAL frequent flyers do.

The choice of seniority, auction, or “pseudo auction” is a difficult one, and largely depends on the options buyers have.

In the case of airlines, loyalty will switch in the cities where viable competition prevails (which, in hub cities, is less and less seen). In the case of directories, being found is critically important to revenue, and unless there are clear substitutes, the market economics will drive to pay higher prices to secure top positioning.

Seniority can still be a factor in the pseudo auction, which could mitigate some senior buyer ire. Other key factors involve of course the extent of the marginal revenue, the “loyalty elasticity factor”™ (i.e. the likelihood of losing highly valued customers), the business’s immediate cash flow needs, offer complexity and communication requirements, and other dynamics.

Abbey Road has extensive experience in helping companies make these trade-offs across many business and industries. The process requires evaluating revenue potential, loyalty elasticity, and other deep pricing techniques.