Better bundling

2013

Bundling is all around us. The cable companies do it, Walmart does it, Prudential Insurance does it, even your local hardware store does it.

So why do they bundle? Why not sell the parts of the bundle separately? There can be many reasons, but more often than not, the main motivation is to generate incremental sales volume even at the expense of margin. To do bundling right is difficult.

In our many years of advising clients, we have probably seen every conceivable bundling mistake possible. Here are some of the most common:

- Over-bundling – This refers to putting too many elements into a bundle, many of which customers don’t even want. It usually starts with competitive pressure in the market place and well-meaning marketing managers wanting to “add value” to justify a price point. More often than not the value-adding elements are value-subtracting as customers don’t want those elements. A good example of this is cable TV where more and more channels (that nobody wants) are added to justify high monthly subscription fees.

- Bundling weak selling products with strong ones – The motivation for this approach is often to “get rid of inventory.” This may actually work, but usually only when the price of the bundle is so low, that the weak product is essentially being given away for free.

- “Forcing” trial via bundling – This is a favorite tactic used by consumer packaged goods companies in wholesale clubs, where they want to promote trial of new flavors by bundling together the new flavored items with the established ones. This may work on occasion, but most consumers want to buy value-packs of their preferred flavor, not variety packs. As a result, the variety packs are usually heavily discounted to “compensate” consumers for talking the risk of buying flavors they may not like and end up throwing away.

What all of these examples have in common is that they try to sell things that people don’t want. And people hate to pay for things that they don’t want. The result is that these “bad” bundles only sell if they are deeply discounted, to a point where the manufacturer is virtually giving away the components that are unwanted.

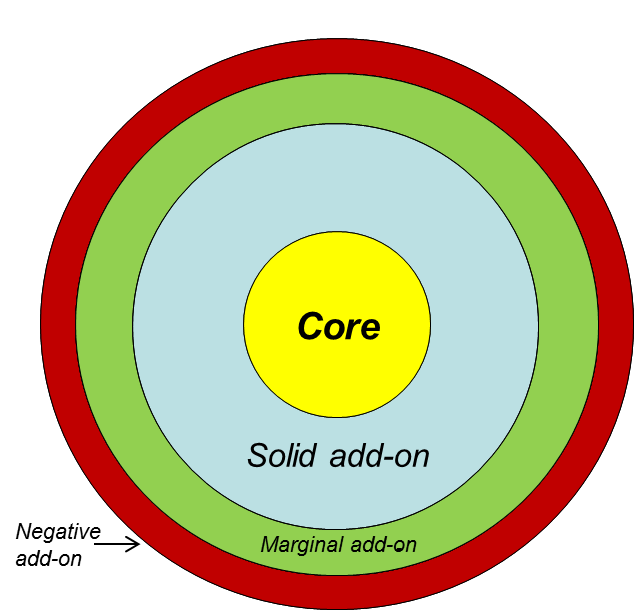

There is a better way to construct bundles. We have a proven, proprietary methodology that analyzes usage and/or purchase data to scientifically construct effective bundles. Our methodology is based on the fact that all structured bundles have a taxonomy (Figure 1) with a core (main reason why customers consider the bundle in the first place) and add-ons which can have more, less or even negative value.

Figure 1 – Bundle Taxonomy

The goal for effective bundling is to identify the core of the bundle, and to determine which potential elements are “worthy” add-ons versus those that are not.

The process entails running correlation analyses to quantify the strengths of the relationships between these elements, and, based on the results, determine which ones belong together and which do not. The strength of the relationships also informs the value of each element as part of the bundle. The outcome is a bundle that will be effective and profitable by attracting incremental purchases.

To learn more about how to build better bundles please go to Resources/Pricing Tools or contact us at 203.514.0515