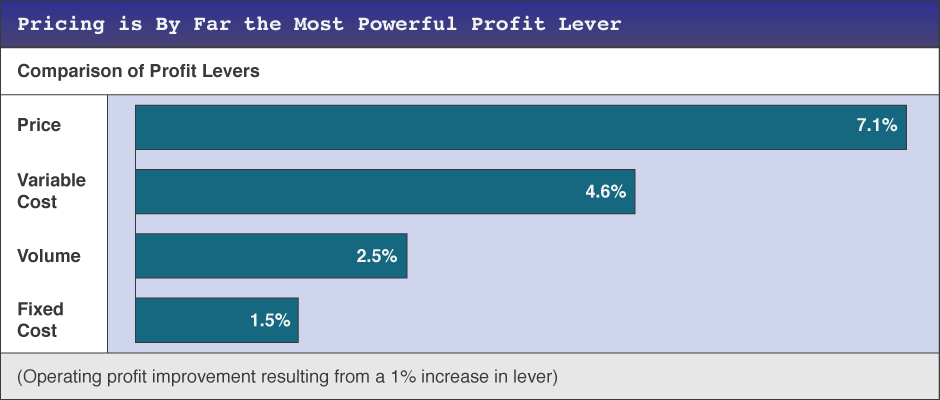

Pricing has a greater impact on the bottom line than cost savings

A one-percent increase in prices for the S&P 500 would increase their net profits by 7-8%, while a cost decrease of one percent increases profits by only 4-5%. A one-percent reduction in the cost of capital or capital employed improves profits by only 2-3%.

The President of the Professional Pricing Society, Eric Mitchell, has commented that compared to other management functions, such as sales, promotions, purchasing, manufacturing, etc., price has been the neglected function.

We believe that reason many managers don’t focus enough on price and brand is that their efforts in these areas don’t seem to bear a linear relationship to revenue growth. In other words, you can double your efforts on price and brand, but this never seems to yield double the revenues. Something as simple as a price increase will work fine one time, fail the next timewith no logic to explain the difference in outcome. Even if an increase succeeds, you’re forced to wonder whether it was as big as it could have been, or whether you’ve left money on the table. How can you know? In every way, results from pricing and branding seem uncertain and arbitrary.

What’s really going on here is not that pricing is uncertain, but that most managers aren’t equipped with the tools required to be confident of their pricing. With better tools management can trace through previously neglected steps in manipulating product and profit, price and cost, brand and price, value and revenue.

Branding is another area where results often seem disconnected from effort. Your business probably devotes significant resources to brand-but can you quantify exactly how this effort improves your top line, your cost position, your bottom line? If not, most likely these resources are being wasted. Contrary to what brand gurus may tell you, brand awareness by itself can be worth very littleand in fact, without a clear value proposition, can be downright harmful.

For example, Isuzu, the maker of economical mid-priced cars, outspent its competitors on advertising on a per-car basis, thereby creating big brand awareness. The only problem was this leap in awareness didn’t help sales: A study shows that few visitors to an Isuzu showroom left having bought an Isuzu, as compared to the preponderance of visitors to Mercedes showrooms who left with a Mercedes. Imagine the needless expense to Isuzu, both in branding and in the sales channel. The Isuzu branding effort resulted in higher selling costs, while Mercedes branding has resulted in lower selling costs – and higher revenues.

While some revolutionary changes usher in hot new markets where demand exceeds supply—and segmentation is unnecessary initially—in more mature markets segmentation is key for revenue maximization.

One size does not fit all. Virtually all major markets have customers who value an offer differently, and who have different spending ability. Different means for reaching a buying decision (e.g. committee decision versus single decision-maker) will show very different characteristics in initial purchase as well as renewal/repeat purchase.

By way of example, we found a data communication equipment manufacturer had to couch its value proposition (and its price quotes) differently depending on whether the buyer was the I/T department, a departmental buyer, purchasing, etc. Each decision maker has different criteria, e.g. departmental purchasers might focus on MIPs per initial purchase price, while more financially driver buyers might prefer $/MIP over 5 years.